[Bracketed sections like this have been added in 2020.]

There is no mistaking that England does come to a conclusion at Land's End. I pull in at a lay-by on the top of a hill and, in the breeze, look around me. There is a 270-degree view of the sea from here, from St Michael's Mount around to Cape Cornwall. Tonight it is deceptively soft and gentle, belying the enduring strength of the last bleak stretch of granite pointing into the teeth of the Atlantic. Suddenly there is nowhere left to go.

But just as civilisation loses interest and the A30 winds down from the dual carriageway just a few miles up the road, here you realise less means more. Here you can sense the age old battle that has gone on between land and sea; land pockmarked with signs of prehistoric man and riddled with forgotten mines, and a sea with a past record in wrecking that demands an awesome respect.

Standing on the hill as darkness falls, I have never been as aware of this battle. It is a heroic panorama. It is no wonder that the Cornish think of themselves as ruggedly independent from the rest of the country. They are surrounded with water; even their border with Devon follows the line of the River Tamar until it is a trickle near the north coast.

I knock on the door of a nearby house to ask for water. A little boy answers, and he is then joined by one of a jumble of young people inside. There is a look of envy when I explain what I'm doing and where I'm going. In the yard outside nature is gradually reclaiming a converted ambulance and a VW Beetle, a reminder of past travels. Maybe this is how it all ends; mechanical breakdown and a slow rehabilitation into four walls. I settle with them, drinking a can of beer while they regale me with stories of benders, alternative sites and the dying breed of sympathetic field owners.

If they were going to settle down, Cornwall is to them a better place than most. One of the men shows me the shed where they earn their livings from weaving baskets. He has country craftsman written all over him. As he shows me around he says: "You know what they say about Cornwall? It's like a Christmas stocking. All the nuts fall to the bottom."

***

I freewheel down to the coast in the morning, to the tip that I remember from my childhood as nothing more than a car park and a tea house. At least, that is how I like to remember it.

Until a few years ago Land's End was little more than a few buildings on a cliff with a car park, not very beautiful I'm told, but where people came to pace the cliffs until they were almost bare of grass and buy postcards and tea. As such it was a fitting scene of things petering out before rather more spectacular elemental forces took over.

|

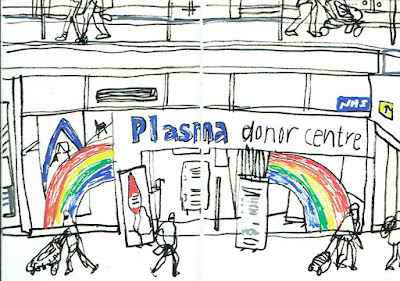

| James Hobbs, Land's End, Cornwall, 1990 |

But this is now changed. The public, it seems, need to entertained in family-sized packages and with this in mind Land's End was bought by the entrepreneur Peter de Savary. It became the relaunch of Land's End. It is, in a region of so many firsts and lasts, the First & Last Theme Park, where, we are told, "the Atlantic Ocean confronts England's romantic last outpost".

It is the romance of freshly made doughnuts, self-service restaurants and information desks, a sprawling amalgam of white buildings to detain you and your wallet on your way to the cliffs that are presented almost as a sideshow. And so, if it all becomes too much and you jump into your car and just drive and drive to escape it all, this is what you will find.

A woman hangs out of a displaced gazebo, wodge of tickets and glossy leaflets at the ready.

"Just you dear? Four pounds please." [Only £6 in 2020! See https://landsend-landmark.co.uk]

Maybe it is a place you enjoy most with children and it makes me feel as if I am kicking down sandcastles to say it detracts from what Land's End is all about, because this really could have been built on the top of any cliff in Cornwall. As with Stonehenge, the way it is presented shows that its significance is just not understood, the emphasis being on packing them in and keeping the cash tills ringing.

The sea is still flecked with surf, even on this increasingly becalmed day, a deception that is unlikely to lure any craft onto the rocks, not least because none are visible. There is nothing serene about it. Waves crash in slow motion over rocks around the Longships Lighthouse about a mile away, hanging unreally in the air. The granite cliff is uneven and ragged, not the most spectacular but the most under siege. At Sennen Cove, about a mile around the coast to the north, it is sheltered enough to be a different day, the sting taken out of it.

|

| James Hobbs, Land's End signpost, Cornwall, 1990 |

One of the most recognised features of Land's End is the signpost that points to cities around the world, the usual point of arrival and departure for those travelling to and from John O'Groats. As I arrived there was somebody just setting out, being photographed before the signpost holding up a copy of the Guardian like a kidnap victim. He is struggling with his rucksack and sponsorship forms for Multiple Sclerosis Charities before setting out to hitch-hike north and then back down again. Land's End's resident photographer gives him a note to deliver to her counterpart at John O'Groats, and he was away on the 870 miles up and 870 miles back.

"See you in about ten days," he said glumly. I could have offered him a lift – I will be near Scotland (in a couple of months).

"We had four here in one day last week," a grey haired lady in the gift shop was telling me. "One came in so late there was hardly a soul here to see them, and the signpost had been taken down, the poor lovey."

There is a selection of photographs in the hotel of some of those who've undertaken this trip, from cycling nudists to wheelchair racers, although it is such a common event now there is nothing extraordinary about it.

There is the hardy air of visitors who have ventured out in the wind and rain swathed in fluorescent waterproofing only to be caught out by fresh sunny weather. We watched it rolling towards us over the sea from behind the Wolf Lighthouse, like a curtain pulled back. Standing on the cliffs today is like a seat in the stalls watching effortlessly spectacular sea and weather. With the wind coming directly from the west, it is a supply of fresh air that has done little more than brush over the Isles of Scilly on the trip over the Atlantic.

The skies are busy with helicopters and small planes heading for the Isles of Scilly, which are just a thin line on the horizon. On the clearest days you can make out the sandy beaches. Their reputation for early flowers and leisurely holidays rather goes against the diet of shipwrecks and smuggling we've been fed in the centre.

But with all this crashing and blowing going on, salt on the lips and warmth of the sun, just why a "multi sensory experience unique in Europe" has had to be created in a great cavernous studio is hard to understand. While we queue to go in, and a girl from Wolverhampton tells her friend, a little too loudly, how her mother had been injured by a sheep in Australia, there is a announcement for those of a nervous disposition that they may be letting themselves in for a rough ride.

|

| James Hobbs, Land's End, Cornwall, 1990 |

Leaning on barrels in a dark open space we are flashed back in history, even unto Neptune himself, to imagined sunken villages now thoroughly submerged and largely forgotten and I gradually came around to the realising, as I suppose I was intended to do, just what a fearful thing that sea stuff can be.

Torn into the modern day, the moment for the nervously disposed arrives in the shape of a simulated rescue by a Sea King helicopter. Lights flashed and spun above us while over the deafening sounds of its whirring engines, orders are barked to us over a megaphone.

I look up, longing for the sight of a rope to descend that can take me away.

James Hobbs, 1990

[Further posts about this journey will follow here soon. This is a link to details about my journey, which started 30 years ago this spring.]

Read on: Caught in the rain on Dartmoor