This is the latest in a series of posts about my journey around England in a camper van in 1990. Read an introduction to this drawing journey around England here.

[Bracketed sections like this have been added in 2020.]

At Tavistock, having loaded the van with food from Gateways and filled it with petrol, climbing the roads towards the moors became ever slower, and it was no surprise to find myself (and the ever present cortege) crawling into dense clouds. Once past the cattle grids it is a relief to be driving along hedgeless roads, except for the tendency of sheep and ponies to wander onto the road. On summer evenings especially they huddle together on the tarmac, which retains its warmth into the night.

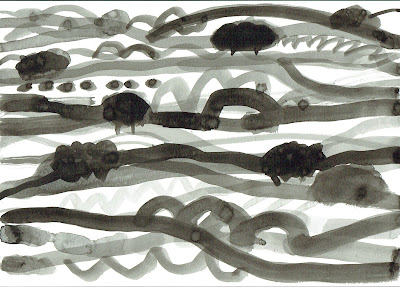

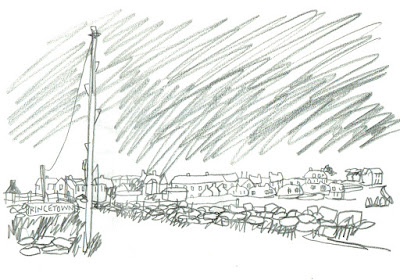

It is cold and miserable turning in to Princetown (top image), the tors occasionally glimpsed through the mists. It is weather that suits the town well enough – it is remote and exposed with a sense of rising as well as falling damp. Down a walled road I get a first view of the prison for which Princetown is best known.

["Mad" Frankie Fraser, the Acid Bath Murderer John Haigh, and Axeman John Mitchell were among its inmates. The prison is due to be closed in 2023 and – just possibly – turned into a hotel.]

There are yellow lines to stop parking by the prison's walls, but a coach has pulled in anyway by the gates, its occupants lurching over to one side to show a wall of faces against its windows. There isn't really so much of the prison to see except these great excluding walls and a barrier rising and falling for cars to enter a line of successive gates. But what there is transfixes. It is like looking at a dead body washed up on a shore; you don't really want to look but you know you must. These blank walls have added significance for being all there is to show for lives spent inside.

|

| James Hobbs, Dartmoor Prison, Devon, 1990 |

The town would not be here without the prison. Built for US and French prisoners of war in the 19th century, the prison and the town itself have struggled to survive. To hold out against elemental forces that threaten to dissolve the very fabric of everything except the tors is almost enough. If Princetown was abandoned tomorrow, you would half expect all remnants of human habitation to be washed into the rivers and streams within months, devouring its past.

Prisoner officers come out in small groups to go to their sad-looking houses up the road. They are disgruntled and reluctant to talk. I have heard on the news that they are voting on taking industrial action today. A few months ago there were prisoners sitting on the roofs of prisons up and down the country, a phenomenon Dartmoor did not entirely escape, a lone figure being picked up by a photographer with a zoom lens from across the moors.

The prison is the town. Either you are trying to make a living in the prison or from the tourism it generates. Otherwise you are a tourist or one of the prisoners that are seen occasionally working out in the fields. The tourist office is empty enough, the man behind the counter startled by my entry. There are photographs of the moor's sunnier days, of streams that tinkle just to look at them, when the terrain is a release rather than a confinement. There is a map on the wall showing the old mining railways that used to run across the moors here.

|

| James Hobbs, Dartmoor Prison, 1990 |

They are gentle walks now through a landscape it is easy to imagine as being unspoiled, but which are really scarred with the quarrying that has gone on over the years. Following one former line just out of the town, I found rabbits hopping around heaps of granite rubble and sheep as surprised as the man in the tourist office. It is hard to get lost with the TV mast perched over the town acting as a marker, but even this appears to move against the drifting clouds.

|

| James Hobbs, abandoned granite blocks for London Bridge, 1990 |

Among the rubble, further around, are the shapes of twelve carved blocks prepared for the building of London Bridge in the 1890s, crooked but far from overgrown. Now they still sit by the rotting wooden sleepers that once held the track. It is the railway that has departed instead. A number went when London Bridge was sold and shipped off to Arizona and some repairs were necessary. It is just down to these dozen now, a bizarre but cheerful reminder of some madder world.

A woman by the road at Two Bridges is pointing out a farm where I could camp when a car speeds by with its hooter on, scattering a group of ponies that stood at the edge of the road. "No offence," she says, "but it is the youngsters that come out of the pubs at night and don't give a second thought – until they see the dent in the bonnet the next morning."

|

| James Hobbs, Dartmoor, Devon, 1990 |

The farm she directs me to is down a track that leads to a small stone bridge among low trees. Pulled in on one side are a couple of long caravans, a lorry and an estate car. They look to be here to stay. A child stares at me through a window as I pass. The farmhouse is further on, the door open showing a messy, deserted kitchen. Two upturned buckets are on the floor and a pile of socks are on the table. I knock and shout, but nobody comes.

Walking back trough the yard they catch sight of me from one of the outhouses where they are watching a rejected calf being fed by another cow. A group of blond-haired children look on too with the young farmers and then we pretend to help by sealing off escape routes as the calf and cow are coaxed back into a field. They seem to know which way to go without our help.

Soon the farmers are telling me what tough land it is to farm, of how it takes social security and family credit to keep them solvent. They have a thousand acres, a huge size, "but it takes that much to keep it profitable up here," she says.

He is young and bearded, and she is a throwback to some sixties pop festival. I ask them if they dislike farming so much why they don't just sell up and go. "Firstly this isn't ours to sell – we're just Prince Charles' tenants – and secondly we are trying to get out," he says. "We work 90 hours a week and still rely on handouts – of course we're trying to move."

So I pay him the 50p they charge for a night camped by the river. On the water's edge are two tents owned by a nurse, his partner and a boy from a special needs school in Wales who skips around the field in a wide arc. They are as vague as he is energetic. In the evening we all go into a pub in Princetown in their Land Rover where I rattle around in the back with their two dogs.

I get on with camping by the river and use it as a base for a few days. I have neighbours who drop in from time to time for a chat. The children from the caravans, Holly, Megan and Luke, bring me a bunch of flowers. There are no toilets or showers, but it is cheap. Occasionally, fleetingly, it even stops raining.

|

| James Hobbs, Widecombe-in-the-Moor, Devon, 1990 |

After a visit to Widecombe-in-the-Moor I drop in at the Warren House Inn, a quiet place in the middle of nowhere. When Morton was here this pub had a fire that had burned for 100 years. It burns on as pathetically as when he was here. Two logs are perched on a thick bed of ash, only the odd spiralling fleck giving away that it is alight at all. The landlord admits it is almost impossible to let it go out.

"Sometimes we go out for the day, down to Plymouth or somewhere, and come back and it will be there looking dead and all you have to do is drop a couple of logs on and it's away again. No problem."

He'd never heard about In Search of England and so he reads about Morton's visit leaning on the bar while I sip my low alcohol cider. The old stuffed fox is gone (the landlord had disposed of one not so long ago) and there are the murmurs of conversation over the clinking of eating and drinking. That this pub is here at all is again thanks to the tinners who once worked nearby. Now it attracts hikers, salesmen and watchers of the useless fire.

Back at the campsite I cook in the van with the rain still falling, listening to Brazil beat Scotland in the World Cup on the radio. I leave the moor in the morning, nearly getting stuck in the muddy field and driving up the road to cheers and waves from the children. I stop in Princetown to do some shopping and take a last look at the prison going in and out of focus through the mist.

The van will not start when the moment comes for me to make my own Dartmoor escape. A man appears from nowhere with a can of WD40, which he sprays liberally around the electrics, and I am gone.

James Hobbs, 1990

|

| James Hobbs, Clovelly, Devon, 1990 |

[Further posts about this trip will follow here soon. This is a link to details about my journey, which started 30 years ago in spring 1990. I'll be posting images from the trip on Instagram.]