This is the latest in a series of posts about my journey around England in a camper van in 1990. Read an introduction to this drawing journey around England here.

[Bracketed sections like this have been added in 2020.]

On the road to Exeter (above), where the slopes become hills and there is no mistaking that Devon is somewhere different, there is news coming through on the radio of a collision off the south coast between a trawler and the oil tanker Rose Bay. The report tells how the trawler crew were more interested in watching the Cup Final on a TV below deck than what they were likely to run into as they floated along [Manchester United and Crystal Palace drew 3-3 after extra time]. The result is an oil slick that is bobbing away at sea, but which may yet meet the very coast I am heading for. All eyes are on the weather forecast and the wind directions.

A strip of road passes along the edge of the River Avon near Bigbury Bay, a quiet, narrow lane that is little higher than the level of the receding water. I have pulled in under the craggy little cliff next to it watching the tide drop as I cook. There are signs of a high tide mark along the road, a line of assorted twigs, but the rider of a horse that passes assures me I should be safe to park here tonight. She says the tides are not so high at the moment, so I shouldn't wake up to water lapping around my bed. Anyway, it will be even quieter later, she goes on, as the road gets completely flooded fat high tide further along, which will effectively cut me off.

|

| James Hobbs, Devon gateway, 1990 |

This estuary would have been one of the most affected had the oil spillage been much worse. Sensitive wildlife areas are still threatened even though booms are being positioned across the mouths of rivers to keep what there is out. In the same way, roads to this stretch of coast have been closed too, to keep out people coming to gawp at the mess there is. “Road closed – no access to beach” signs block the routes to the blackened shoreline.

The warnings for people to stay away have worked. The roads are largely deserted. When I later find my way down to the beach at Bigbury, there are only a few cars in the car park and a couple of people walking across from the pub on the island. There are tyre marks in the sand and I can persuade myself that in the wind I can smell disinfectant. But of the sludgy oil and blackened wildlife that are pictured in the local paper, there is no sign.

[About 1,100 tonnes of crude oil were spilt in the Rose Bay collision, polluting about 12 miles of the Devon coast. I'm not sure how I missed the damage: it was reported in Hansard that Challaborough beach, close to where I camped for the night, was damaged by oil up to 18 inches deep.]

***

True enough, I am not flooded out in the night. The road is still wet, but I have lost no sleep. I eat my breakfast cereal watching swans and a heron on the river, untouched by oil from the Rose Bay, and then head further west.

Plymouth is studded with plaques and memorials to prove its great pride in its history. They pop up everywhere. Nowhere is this more evident than on the Hoe, a vast green brow along the front that looks over the Sound. There is Smeaton's Tower which used to be the lighthouse perched out on Eddystone Rock, and a statue of the Sir Francis Drake, the English explorer [and slave trader]. Today he seems to be waiting at a bus stop, having to be content with the view of the back end of a line of vintage buses that are being clambered and drooled over by enthusiasts.

[Drake's statue has, for now, survived the toppling that those of other figures with links to slavery and Britain's brutal colonial past have undergone in the wake of George Floyd's killing by police in the US.]

|

| James Hobbs, Drake's statue, Plymouth Hoe, 1990 |

As if this wasn't enough the Army Display Team are on hand too, standing over young boys holding rifles and explaining the finer points of the camouflaged tanks and jeeps. The last time I had seen this such a vehicle was on the sea front at Bournemouth keeping an eye on the Leeds supporters. The idea of this event is probably to get the kids before they get you. It is mostly young families looking around, some with pushchairs, as nonchalantly as if it was a village fete, kids pulling dads towards different stands.

"Fire a service rifle. Five shots for 20p," reads a sign. A few youths shoot down a small gap at the back of a camouflaged lorry.

It is not surprising to find this here because Plymouth's name has been made by war and by the sea, and to look out from the Hoe, it is easy to see why. It is a marvellous harbour view, a stage that makes each arrival and departure an event. There is everything from dinghies to cross channel ferries passing through it even now.

But what it also does is tame the idea of what it is to cross oceans. It is like a gentle introduction, seductive, impossible to ignore, its two headlands a gateway that asked to be passed through. There is a terrace down to the water's edge and bare rocks, cafes, deckchairs and two floating white islands offshore where swimmers are sitting and resting. The Rose Bay cannot be far from their minds.

There is another outbreak of plaques at the Barbican, the old fortified area of Plymouth whose narrow streets show that it, at least, survived the bombing raids. It was from here the Pilgrim Fathers left on the Mayflower. Number 9, the house where it is claimed at least some of them stayed the night before they set sail is no longer the coal merchant of Morton's time, but a shop selling junk art to the American tourists, who are in no short supply.

But it is not really a tourist atmosphere here; it is a place to see and be seen on this afternoon, bump into friends, watch people pass from the benches. The narrowness and irregularity of the Barbican stands out – after the massive destruction of the second world war Plymouth's centre was rebuilt with sweeping dual carriageways and straight, yawning thoroughfares. For a while it was as if Chicago had come to Devon as a grid system of roads was laid out and 14 storey buildings were called skyscrapers. Built for the age of the car, many of the shopping streets are closed to them now, filled instead with fountains, trees and playgrounds. Charles Church remains roofless as a memorial to those lost in the war, its shell embalmed in the middle of a roundabout. Plymouth is still getting used to being its new self.

|

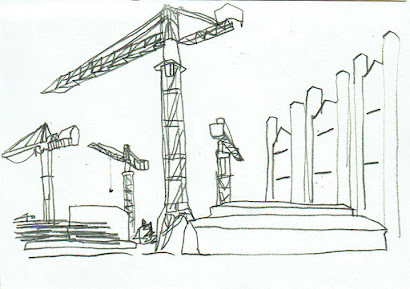

| James Hobbs, Devonport Dockyard, 1990 |

The city's dockyard at Devonport, started under William of Orange, struggles to survive in these post Cold War days. This is good news and bad news to Plymouth's workers of course, but for now it survives in competition with Scottish dockyards, fighting to have nuclear submarines in its waters. In search of an entrance to the waterfront, I have turned down a road to be stopped by a policeman.

"Sorry sir, no public access here, but if it's cranes you're looking to draw, may I suggest Cornwall Beach. Right at the lights, left at the mini-roundabout, down a cobbled street..." His suggestion is perfect. The road, lined with blocks of flats, slopes down to the water and a couple of pubs, but is dominated by the view of the bow of a ship. There is about 10 feet of shingle and a few rowing boats. Music is in the air and children are playing in the street.

|

| James Hobbs, Cornwall Street, Plymouth, 1990 |

"I did a drawing of a balloon at school today," a little girl says, and runs to get it, but comes back with her younger brother instead. They sit and chat with me as I draw, oblivious to warnings about talking to strangers. When I tell them I am going to Cornwall, she tells me they have never been, and yet there it is just across the River Tamar from us.

The Sound narrows at Devil's Point and opens again into the deep landlocked harbour that is marked with cranes and docks. For all the prosperity it has brought Plymouth it is rough and stark, an area used to dealing with the demands of sailors finally making it ashore after voyages, used to the freight thundering in and out and the tourists on their way to France and Spain on the ferries.

|

| James Hobbs, Tamar bridges, 1990 |

For those that have charged down the A38, skirting the south of Dartmoor on their way to Cornwall, there is the Tamar Bridge to mark the event. It stands beside Isambard Kingdom Brunel's suspension bridge built 100 years previously, and together they make an interesting pair. While a woman feeds herself and her dog with ice-cream by the next car, I watch the trains cross the bridge, and disappear from view until they cross a more distant viaduct.

But rather than take the bridge, I stick to Morton's route and take the Tor Ferry. I queue for longer than the trip takes. Immediately things do change and something does take over. The roads are quiet and the sea is calm as I make along the coast, but it is a step that signifies that the land is running out, narrowing, and soon we will be left at the tip of Land's End.

James Hobbs, 1990

[Further posts about this journey will follow here soon.]

Read on: Through the lanes of Cornwall

No comments:

Post a Comment